What is Helicobacter pylori?

H. pylori is a bacteria that infects the stomach lining in humans. It is a common cause of peptic ulcers and is strongly associated with stomach cancer. More than half of the people worldwide are thought to have H. pylori, with most infections acquired during childhood. Most people are unaware they have H. pylori because they do not have symptoms, but those who develop symptoms of peptic ulcers may need to see a doctor to seek treatment to prevent further development of chronic illnesses such as chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric cancer.

Download the CDC Factsheet

References:

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. (2017, May 17). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/h-pylori/symptoms-causes/syc-20356171

Driscoll, L. J., Brown, H. E., Harris, R. B., & Oren, E. (2017). Population Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Helicobacter pylori Transmission and Outcomes: A Literature Review. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 144. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00144

How common is H. pylori infection?

It has been estimated that 30–40% of the U.S. population is infected with H. pylori.

Reference:

Peterson WL, Fendrick AM, Cave DR, et al. Helicobacter pylori-related disease: Guidelines for testing and treatment. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1285–91.

Prevalence and Incidence:

H. pylori prevalence and incidence differ by geography and race. Prevalence refers to the total number of people that have a disease at a given time, while incidence refers to new infections of a disease in a given time period. In general, H. pylori prevalence is higher in developing countries and declining in the United States. The incidence of new infections in developing countries reflects 3-10% of the population each year newly infected compared to 0.5% in developed countries. In developing countries, the infection is generally acquired at a young age.

In the United States, H. pylori prevalence is higher in Hispanics, African Americans, and the elderly. H. pylori prevalence is estimated at around 60% in Hispanics, 54% in African Americans, and 20% in whites. Infection rates are similar for men and women. In the United States, the estimated prevalence is 20% for people younger than 30 and 50% for those older than 60.

References:

Rosenberg JJ. Helicobacter pylori. Pediatr Rev. Feb 2010;31 (2):85-6; discussion 86.

Everhart JE, Kruszon-Moran D, Perez-Perez GI, Tralka TS, McQuillan G. Seroprevalence and ethnic differences in Helicobacter pylori infection among adults in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2000 Apr;181(4):1359-63. Epub 2000 Apr 13.

What illnesses does H. pylori cause?

Complications associated with H. pylori infection include:

- Ulcers. H. pylori can damage the protective lining of your stomach and small intestine. This can allow stomach acid to create an open sore (ulcer). About 10 percent of people with H. pylori will develop an ulcer.

- Inflammation of the stomach lining. H. pylori infection can irritate your stomach, causing inflammation (gastritis).

- Stomach cancer. H. pylori infection is a strong risk factor for certain types of stomach cancer (non-cardia).

Reference:

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. (2017, May 17). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/h-pylori/symptoms-causes/syc-20356171

What are the symptoms of ulcers?

- An ache or burning pain in your abdomen

- Abdominal pain that’s worse when your stomach is empty

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Frequent burping

- Bloating

- Unintentional weight loss

Reference:

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. (2017, May 17). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/h-pylori/symptoms-causes/syc-20356171

Who should be tested and treated for H. pylori?

Patients with active peptic ulcer disease (PUD), history of PUD, low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, or a history of endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer (EGC) should be tested for H. pylori infection. Other patients with dyspepsia who are under 60 years old should consider getting non-endoscopic testing for H. pylori. Those who test positive should be offered antibiotic therapy to eradicate the bacteria.

Patients with dyspepsia who have undertaken endoscopy should be evaluated for H. pylori by taking gastric biopsies. These patients are strongly suggested for eradication therapy.

Patients taking long-term, low-dose aspirin should be tested for H. pylori infection to reduce the risk of ulcer bleeding, and eradication therapy should be offered to those who test positive.

Patients taking chronic treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) should be tested for H. pylori infection, and eradication therapy should be offered to those who test positive.

Patients with iron deficiency anemia should be tested for H. pylori, and eradication therapy should be offered to those who test positive.

Adults with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) should be tested for H. pylori infection, and eradication therapy should be offered to those who test positive.

References:

Armand, W. (2017, April 05). H. pylori, a true stomach “bug”: Who should doctors test and treat? Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/h-pylori-a-true-stomach-bug-who-should-doctors-test-and-treat-2017040511328

Go, M. F. (2003, September 9). Helicobacter pylori: When to Test and How to Treat. Retrieved from https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/460810

How is H. pylori infection diagnosed?

Without Endoscopy

|

Stool/fecal antigen test |

Detects the presence of H. pylori antigen in a stool sample |

|

Urea breath test |

A person drinks a solution containing a low level of radioactive material that is harmless or a nonradioactive material. If H. pylori is present in the person’s gastrointestinal tract, the material will be broken down into “labeled” carbon dioxide gas that is expelled in the breath. |

|

H. pylori antibody testing |

Test not recommended for routine diagnosis or for evaluation of treatment effectiveness. Detects antibodies to the bacteria and will not distinguish the previous infection from a current one. If the test is negative, then it is unlikely that a person has had an H. pylori infection. If ordered and positive, results should be confirmed using stool antigen or breath test. |

With Endoscopy: tissue biopsy sample obtained; good tests but less frequently ordered because invasive

|

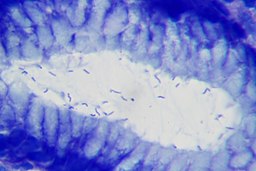

Histology | Tissue is examined under a microscope by a pathologist, who will look for H. pylori bacteria and any other signs of disease that may explain a person’s symptoms. |

|

Rapid urease testing | Fragments of H. pylori DNA are amplified and used to detect the bacteria, primarily used in a research setting. |

|

Culture |

The bacteria are grown on/in a nutrient media; results can take several weeks. This test is necessary if the health practitioner wants to evaluate which antibiotic will likely cure the infection. |

|

PCR (polymerase chain reaction) |

Fragments of H. pylori DNA are amplified and used to detect the bacteria; primarily used in a research setting. |

The stool antigen test and urea breath test are recommended for the diagnosis of an H. pylori infection and for the evaluation of the effectiveness of treatment. These tests are the most frequently performed because they are fast and noninvasive. Endoscopy-related tests may also be performed to diagnose and evaluate H. pylori but are less frequently performed because they are invasive.

Reference:

H. pylori Testing. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://labtestsonline.org/understanding/analytes/h-pylori/tab/test

Are there any long-term consequences of H. pylori infection?

There is an association between long-term infection with H. pylori and the development of gastric cancer. Globally, 80% of the 1 million new cases annually are attributed to the treatable infection.

References:

Helicobacter pylori: Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers. Centers for Disease and Control. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ulcer/files/hpfacts.pdf

Herrero R, Parsonnet J, Greenberg ER. Prevention of Gastric Cancer. (2014) JAMA. 312(12):1197–1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10498

How do people get infected with H. pylori?

The most common route of H pylori infection is either oral-to-oral or fecal-to-oral contact. Some evidence points to transmission from contaminated food or water.

References:

Helicobacter pylori Infection. (2017, October 23). Retrieved from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/176938-overview

Bui, D., Brown, H. E., Harris, R. B., & Oren, E. (2016). Serologic Evidence for Fecal-Oral Transmission of Helicobacter pylori. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 94(1), 82–88. http://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.15-0297

Risk factors:

Living with someone who has an H. pylori infection increases the risk of infection. People may also be infected if someone who prepares their food does not wash their hands properly. Those who have an immediate relative with a history of gastric cancer are also at increased risk for infection.

Living in crowded and unsanitary conditions without a reliable supply of clean water increases the risk of H. pylori infection. People emigrating from geographic areas with high rates of gastric cancer are also at increased risk.

References:

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. (2017, May 17). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/h-pylori/symptoms-causes/syc-20356171

Brown, L. M. (2000). Helicobacter Pylori: Epidemiology and Routes of Transmission. Epidemiologic Reviews, 22(2), 283-297. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018040

What can people do to prevent H. pylori infection?

Helicobacter pylori bacteria are present in contaminated food and water. Therefore, avoiding these sources (e.g., floodwater, raw sewage.) is important. Washing hands thoroughly with warm, soapy water after using the restroom and before eating also may help prevent infection. Eating utensils and drinking glasses should never be shared since the bacteria can be spread through saliva.

References:

Helicobacter Pylori Infection Prevention. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.healthcommunities.com/helicobacter-pylori-infection/prevention.shtml

Dimitriadi, D. (2014). Helicobacter pylori: a sexually transmitted bacterium? Central European Journal of Urology, 67(4), 407–409. http://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2014.04.art18

Treatment options (evidence-based first-line treatment strategies for providers in North America):

|

Treatment Name |

Description of drugs |

Time Period |

Suggested for |

|

Clarithromycin triple therapy |

Proton-pump inhibitor (PPI), clarithromycin, amoxicillin/metronidazole |

14 days |

Regions where H. pylori clarithromycin resistance is <15% and in patients with no history of macrolide exposure |

|

Bismuth quadruple therapy |

PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, nitroimidazole |

10-14 days |

Patients with previous macrolide exposure or who are allergic to penicillin |

|

Concomitant therapy |

PPI, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, nitroimidazole |

10-14 days |

First-line treatment option (strong recommendation) |

|

Sequential therapy |

PPI and amoxicillin; then PPI, clarithromycin, and a nitroimidazole |

5-7 days; then 5-7 days |

First-line treatment option (conditional recommendation) |

|

Hybrid therapy |

PPI and amoxicillin; then PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, nitroimidazole |

7 days; then 7 days |

First-line treatment option (conditional recommendation) |

|

Levofloxacin triple therapy |

PPI, levofloxacin, amoxicillin |

10-days |

First-line treatment option (conditional recommendation) |

|

Fluoroquinolone sequential therapy |

PPI and amoxicillin; then PPI, fluoroquinolone, and nitroimidazole |

5-7 days; then 5-7 days |

First-line treatment option (conditional recommendation) |

Reference: Chey, W. D., Leontiadis, G. I., Howden, C. W., & Moss, S. F. (2017). ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol, 112(2), 212-239. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.563

Other resources:

General information on H. pylori

CDC Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers

NIH National Cancer Institute: Helicobacter pylori and Cancer

Kids Health: Heliobacter pylori Infection

Epidemiology

University of Arizona College of Public Health: H. Pylori Prevalence and Incidence

Diagnosis

Kids Health: Stool Test H. Pylori Antigen

American Association for Clinical Chemistry (AACC): H. pylori Testing

This factsheet has been created by Eyal Oren, Ph.D., and H. pylori workgroup members. Last update: October 31, 2017. The workgroup may be contacted at eoren@sdsu.edu. Used with permission.